By: Johanna Jordan

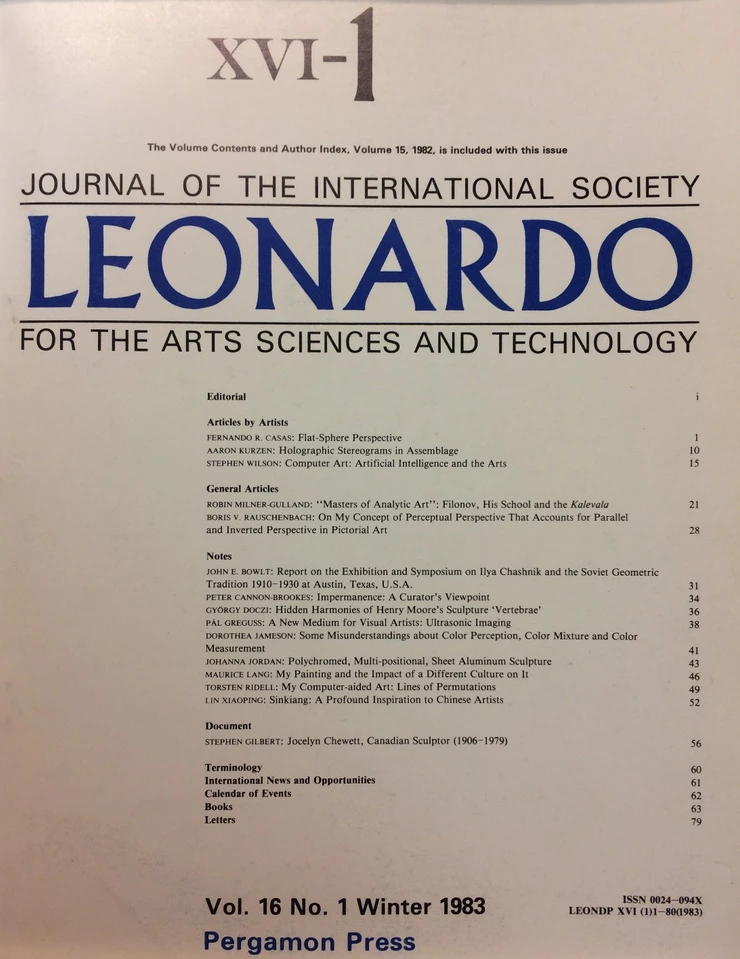

Publication: LEONARDO: Journal of the International Society for the Arts Sciences and Technology – Volume 16, No. 1, Winter 1983 – Pergamon Press

Original Article Location: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/599499/summary

1. Statement

There is a tension at the juncture of planar surfaces, in the edges which run straight or curved, and this property intrigues me. It has inspired me to develop a sculptural method utilizing sheet aluminum.

A rigid, yet flexible material, aluminum sheeting has led me in turn to construct forms with surfaces bending and flattening, meeting on another, and resolving into curved edges. The method has also permitted me to build holes and voids into a piece, setting up contrast with solid form and creating an interplay of negative and positive space. Since metal paints bond will with sheet aluminum, I have been allowed the additional freedom of painting my pieces in panels of hard-edged colors. These interact in a contrast of advancing and receding tones. My hope is that these three elements should play together in assort of counterpoint. And it is this final unification of edge, space and color that leads to my concept of multiple positioning; A piece that works can be set on various of its surfaces, each position showing a different relationship of the elements (Figs. 1-3).

2. Aesthetic Craft

Architectural pieces of the type I create are often made from detailed drawings, so it may seem unorthodox that I do not use this technique. I work directly in aluminum and urethane from a rough, mind’s-eye image and perhaps a few thumbnail sketches. This is partly owing to the nature of aluminum sheeting, which tends to buckle and bend along unpredictable contours; also, it might resist the shapes into which one tries to mold it. More important, however, is the innate complexity of a multifaceted form, multiplied still further by the demands of variable positioning. This is nearly impossible to conceive in the two dimensions of a drawing; furthermore, such a drawing, if actually produced, would be too confining for creating a three-dimensional form.

The mental image which begins my creation is generally a silhouette. I always start with a flat plane after deciding on the general size of the sculpture. I sketch this on paper to make a pattern, and then transfer it to an aluminum sheet. After cutting out the shape with power tools, I line the inside surface with a sheet of urethane foam trimmed to match the metal form. Then I build up and around this initial piece, gluing the foam-lined panels together with epoxy, but always keeping the original form in mind, and seeking the most satisfying plane for each position. It is by using a mirror, however, that I achieve my multi-positional concepts, because as I build the piece, I continuously rotate it, turning it upside down, right-side up, and so on, viewing the reflection as well as the piece itself from every aspect. A plane is not right until it works from all positions.

As a work progresses, it may depart from its original form. Occasionally a random element finds its way into the piece, changing it into a different form entirely, and the transformation is intriguing and exciting. In fact, it seems that I need the freedom to leave the original concept, especially during the construction of large pieces for which I sometimes do make maquettes. In cases like these, I often find it necessary to adjust or change the design mid-project to suit the magnified scale; I must struggle to resist the inhibition that a rigid plan like a maquette can impose. I need to work as freely as possible to keep the form from going lifeless.

3. Construction

Work on these pieces falls into two phases: construction and painting.

Construction is part of a process I developed some years ago to make large pieces manageable. It was patiently obvious that in order to work alone, yet still create large pieces, I would have to find strong, lightweight materials and develop the means to craft them. Thin-gauge aluminum sheeting combined with high-density urethane foam proved to be a fine solution. By gluing sheets of foam approximately 2.5cm thick to the aluminum panel, I could strengthen the metal, making it far more rigid than the metal sheet alone, yet add relatively light weight.

The final product turned out as light as hoped, and aside from the benefits to me in handling, the lightness delighted my clients who were able to move their pieces freely about to change their positions. An added benefit was the cost, not to mention production speed. Urethane foam and aluminum sheeting are far less expensive than traditional materials like bronze or stone, and the process of construction proceeds at a much greater – consequently, freer – rate. But the greatest benefit of all was one I had never anticipated; the lightness allowed me to pursue my concept of multiple positioning.

Large though the piece may have bee, I was able to push it about during the course of construction, turning it over, standing it on end, laying it to one side then the other. This became a natural part of my method. It was inevitable, perhaps, that the method became the aesthetic.

The largest piece I have made with this process is 2.7m high (Fig. 4, Slide #17). Larger dimensions would require thicker aluminum, which would lend itself to welding. Welding would become practical because a thicker aluminum sheeting does not pucker and bend like sheeting of a thinner gauge.

The construction, however, must be structurally sound; it must meet the requirements of strength and internal support, as well as of beauty and form. Every panel should strengthen the adjacent panels, and where this support is insufficient, I use an inner skeleton to reinforce the weak area. Should extra support not be necessary, the piece remains hollow.

4. Painting

The second phase is painting; it utilizes a spray rig and a process identical in its essentials to automotive painting.

Once the foam/aluminum form is finished, I sand the surfaces to a smooth, clean finish. I file the edges so they meet evenly and fill with epoxy the areas that do not meet cleanly. Since flat, even planes are necessary for achieving a glossy, undimpled finish, I fill in any dents or hollows with epoxy filler and, when it dries, sand it flush with the surrounding surface. Next, I clean the metal and paint it with automotive primer. This requires a rig consisting of a spray gun combined with an air compressor.

For reasons of paint flow and color separation, each panel must be treated individually. So I use masking tape and paper to shield the adjacent areas while treating the panel in question. This panel-by-panel approach at times becomes exceedingly tedious – the paint often runs or dust settles on the wet surface, marring the finish – and must be repeated many times. But ultimately it results in the proper sheen (Figs. 5, 6 – Slide #17).

As for the paint itself, I used acrylic enamels for several years. Recently, however, I have switched to acrylic lacquers of the sort used for fine automotive finishes. Lacquers dry much more quickly, accumulating far less dust and speeding the entire production process. I should mention that because automotive paints in general are extremely volatile and potentially toxic, I paint while wearing a gas mask and working in a chamber ventilated by a high-capacity drawing fan.

The choice of colors depends on such qualities as relative values, the juxtaposition of warm and cool, and contrast. All these aspects should combine to create a sense of rhythm, of inherent movement separate from the sculptural design (Color Plate 1).

5. Final Remarks

Sheet aluminum has its own, unique limitations. It can be cut, bent and glued, but beyond that there is not much one can do with it. Admittedly, it is a stiff, restricting medium, far less responsive than clay or bronze. And yet, in some inexplicable way, it seems compatible with my sensibilities. It is precisely the limitations that have freed me to develop my own style, for they have focused my attention on the three aspects that I find most rewarding. For one, I have been able to indulge my love of color – something that traditional sculpture denied me ever since my early years in painting. For another, the pure, geometrics for has kindled an interest in negative-positive space and prompted me to explore new relationships. Finally, working on a large scale has proven most gratifying, stimulating my interest as well as my productivity.

As to where this approach will lead, I cannot venture to guess. I can only say that, for me, experimenting with three-dimensional forms seems to fulfill a deep, subconscious need which acts as a sort of invisible beacon that directs one along lines of aesthetic cause and effect. Following such a course and arriving at a final, unique form is a pleasure that words cannot express. It is a process that keeps one flexible in creative concept but firm in aesthetic intent.